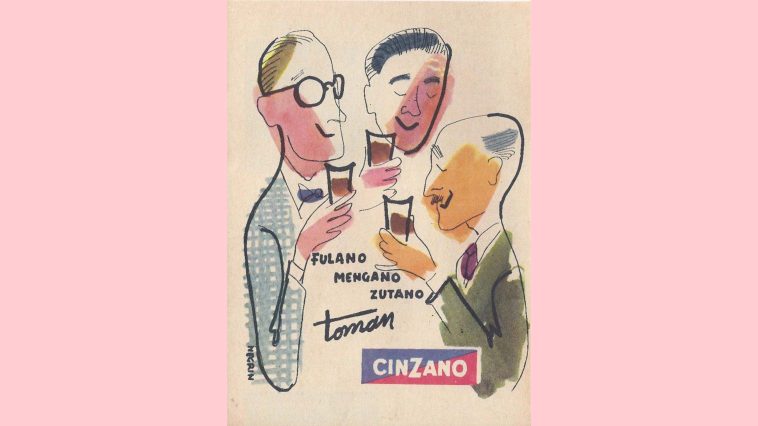

If you study Spanish long enough, sooner or later you will hear the words Fulano, Mengano and Zutano. These names don’t really belong to anybody, but they are used to talk about a person without saying the real name, or when the name is not important. For example, someone can say “Fulano me dijo que…” or “Estaba hablando con Mengano”. In English, the closest idea is the expression “Tom, Dick, and Harry”, or sometimes just “so-and-so”. The meaning is the same: we are not talking about a specific person, just “some guy.”

The origin of these words is very old. Most scholars believe they entered Spanish through Arabic during the Middle Ages, a time when the Arabic language had a huge influence on the Iberian Peninsula. Fulano comes from the Arabic fulān, which means “so-and-so” or “a certain person.” From there, the other names like Mengano and Zutano were created to make a trio that sounds complete and even a little funny.

It is also good to know that these words can change gender. So, if the conversation is about a woman, people can say Fulana, Mengana or Zutana. They work in the exact same way, just with the feminine form. Very often you will also hear them in diminutive form: Fulanito, Menganito, Zutanito. In many cases the diminutive adds a sarcastic or ironic touch, as if to say “that little so-and-so” instead of just “so-and-so.”

Spanish is not the only language that does this. In Portuguese, speakers use Fulano, Sicrano and Beltrano, which play the same role. In Italian, there is Tizio, Caio e Sempronio, three old Roman names that survived as a way to talk about imaginary people. In French, the usual expressions are different, like “Untel” (literally “such a one”), but the idea is still the same. In Catalan, the words are Fulanet, Menganet i Zutanet, very close to Spanish but with the typical Catalan endings.

These names are an important little cultural detail. They show how languages invent imaginary characters to make everyday talk easier. And just like English speakers say “any Tom, Dick, or Harry”, Spanish speakers will always have Fulano, Mengano, Zutano, or even Fulana, Mengana, Zutana, and sometimes sarcastic Fulanito, Menganito, or Zutanito ready to appear in the middle of a conversation.

There is also perengano or perengana, a variation that usually appears when you need to add “one more person” to the imaginary group. It’s like saying “so-and-so number four.” On top of that, the diminutive perenganito (or perenganita) makes it sound even more sarcastic, far-fetched, or ironic, almost as if you are exaggerating the idea of a completely random, unimportant character. For example: “Y al final llegó perenganito a opinar también”.

Y a todo esto, how do they say Fulano in Arabic, if that word came to Spanish from Arabic many centuries ago?

The word Fulano actually comes from Arabic. In Classical Arabic they used the word fulān (فُلان), which simply means so-and-so. For example: ja’a fulān means “Fulano came,” and qala fulān means “Fulano said.” This way of speaking was very common in Al-Andalus, the Arabic-speaking Spain of the Middle Ages, and from there it passed into Spanish.

Even today in Arabic, if they want to say something like “Fulano, Mengano and Zutano,” they usually repeat the word fulān, or they say fulān wa ʿillān (فلان وعلان), which means “so-and-so and so-and-so.” So Spanish kept Fulano directly from Arabic, and later added Mengano and Zutano as playful inventions to complete the trio.